Limitations of DNS-based geographic routing

Notice: This article is more than 5 years old. It might be outdated.

Various Internet services and offerings - such as AWS CloudFront - rely on geographic routing, also known as geolocation or geo-locational routing. And with Amazon Route 53 you can build your own geographic routing enabled services. The basic concept behind this capability is to return a DNS answer for an endpoint that is physically closest to the requestor. In the case of AWS CloudFront this would be the closest edge location, while for a service that you build yourself it might be the decision between an Amazon Elastic Load Balancer endpoint in the us-west-2 (Oregon) or in the us-east-2 (Ohio) region.

This post will look at how geographic routing works, how you can validate the interaction of it with your service and what the expected limitations of the service are.

Geographic Routing

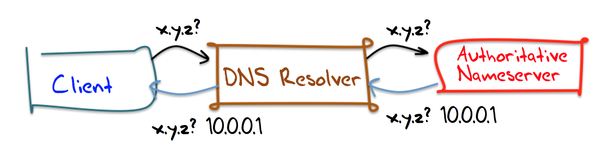

To understand how geographic routing works we first need to have a look at DNS resolution via DNS Resolver. Figure 1 shows a simplified representation of this mechanism, where a client connects to a local DNS Resolver, which then initiates and sequences the queries that ultimately lead to a full resolution (translation) of the resource sought. While depicted in an overly simplified way, this includes querying the Authoritative Nameserver for the interested record by the DNS Resolver.

For geographic routing the “magic” happens during this interaction of the DNS Resolver and the Authoritative Nameserver: The Authoritative Nameserver will respond with a record set that depends on the querying DNS Resolver, ideally its location. In order to accomplish this, the Authoritative Nameserver must be able to calculate the desired mapping based on the location information of the DNS Resolver and the desired mapping of a certain location to an origins record set.

With this the Authoritative Nameserver would e.g. respond to the querry for www.example.com with us-west-2.www.example.com (and its subsequent resolution to an actual IPv4 or IPv6 address), while the DNS Resolver’s IP address is believed to be closer to the AWS Oregon region and with us-east-2.www.example.com, in case the Resolver is closer to the AWS Ohio region.

To do so, the Authoritative Nameserver will use the IP address information for the DNS Resolver to calculate the geographic location. A common service provider for IP Address to location mapping data is Maxmind, which is frequently used for this purpose. An example is the Howto Guide for implementing geographical routing with BIND, which incorporates this GeoIP database.

And while AWS does not publicly divulge information about the source of the used IP address mapping data, Amazon Route 53 uses the same principle.

Limitations of the DNS Resolver location information

At this point you probably already guessed that the Authoritative Nameserver making a routing decision based on the DNS Resolvers location might not be the best approach. That’s because Client and Authoritative Nameserver might not actually be geographically close to each other. What if a client in San Francisco, CA is using a DNS Resolver in New York, NY? While we would want this client to be served by e.g. a CDN Edge location in the San Francisco, CA area, due to the location information attached to the DNS Resolver, that client is actually served by a CDN Edge location in New York, NY.

Looking at Figure 1 again, we can see that the cause for this undesired behavior is that the Authoritative Nameserver only “sees” the DNS Resolver via its IP source address. The Authoritative Nameserver is not aware of the client and therefore has no knowledge of its location. Wouldn’t it be great if the Authoritative Nameserver actually received information about the Client as part of the query request? This would allow the Authoritative Nameserver to respond based on the geolocation location information of the Client instead of the DNS Resolver. That’s where ENDS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) comes into the picture.

EDNS0-Client-Subnet extension

EDNS0 is an extension mechanism for the DNS, which expands the size of several parameters of the DNS protocol for increasing functionality of the protocol. One such increased functionality is EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS). The EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) extension allows a recursive DNS Resolver to specify the network subnet for the host on which behalf it is making a DNS query. Therefore the Authoritative Nameserver will gain insight into the location of the client based on GeoIP information.

Unfortunately not all DNS Resolvers support EDNS0-Client-Subnet. You can find support in frequently used public resolvers, such as Google’s Public DNS Resolver, OpenDNS, and Quad9. Other public resolvers such as CloudFlare do not support it.

If you want to check if your Resolver supports EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS), you can use a special Google debugging hostname as outlined in the AWS Support article “How do I troubleshoot issues with latency-based resource records and Route 53?”. With this hostname the command dig +nocl TXT o-o.myaddr.l.google.com @<DNS Resolver> will not only show you the IPv4 or IPv6 address of the DNS Resolver that is seen by Google’s Authoritative Nameserver. If supported it will also show the client subnet as provided via EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS).

Below is an example run from an Amazon EC2 instance within the US-West-2 (Oregon) region against the Google Public DNS resolver:

ubuntu@ubuntu:~$ dig +nocl +short TXT o-o.myaddr.l.google.com @8.8.8.8

"2607:f8b0:400e:c09::10f"

"edns0-client-subnet 54.186.33.212/32"

We can clearly see that Google’s Resolver supports EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS).

Similarly on the CDN side support to actually leverage the EDNS0-Client-Subnet provided information is not universal. Amazon CloudFront added support in 2014. Also Amazon Route 53 supports EDNS0-Client-Subnet as part of routing policies.

RIPE Atlas

In this post we will use RIPE Atlas to check the performance of a geographic routing enabled DNS entry.

RIPE Atlas is a global network of hardware devices, called probes and anchors, that actively measure Internet connectivity. Anyone can access this data via Internet traffic maps, streaming data visualisations, and an API. RIPE Atlas users can also perform customised measurements to gain valuable data about their own networks.

I highly recommend you to consider hosting a RIPE Atlas probe yourself. Not only will you benefit from the data that it collects on your Internet connection, but it will also allow you to run customized measurements against various Internet targets. And in the end every additional RIPE Atlas probe will benefit the overall Internet community.

Here we will be using RIPE Atlas customized measurements to investigate the performance of DNS-based geographic routing.

Test Setup

Amazon Route 53 Setup

For this article the test setup will consist of fictional origins where we want to steer traffic to via geographic routing. The test will focus on the US with one origin in the US East coast and one origin in the US West coast.

A third origin will be placed into Kansas. With IP location based data a mostly unknown lake in Kansas takes over a special meaning: The Cheney Reservoir is close to the geographical center of the continental US. As such the IP location company Maxmind places all IP addresses for which it has no more information than that it is located somewhere in the US, at this location. It is estimated that over 600 Million Internet IP addresses point to Cheney Reservoir. In the past Maxmind placed these IP addresses into the backyard of a Kansas family, whose life was turned upside down as a result.

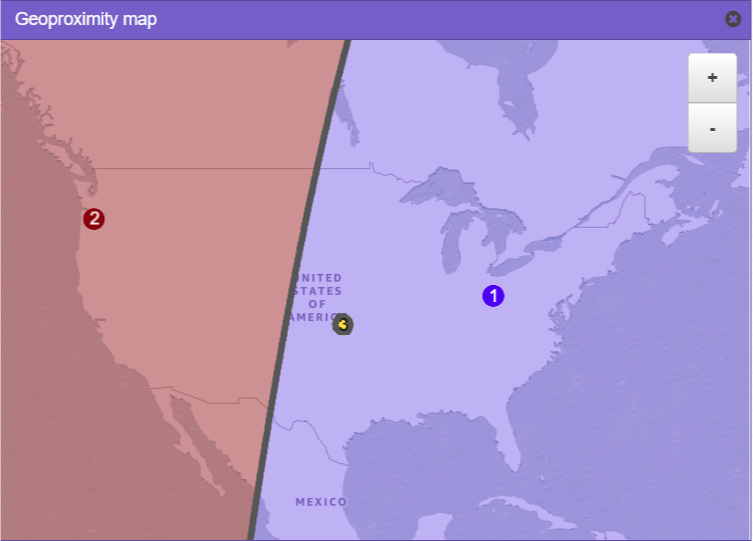

We will model this setup with AWS Route 53 Geoproximity routing, where the AWS regions US-East-2 (Ohio) - as the US East coast location - and US-West-2 (Oregon) - as the US West coast location - receive neutral bias of 0. The origin at Cheney Reservoir receives a large negative bias, to create a small circle of a few miles around this area.

The expected geoproximity routing should look like depicted in Figure 2.

The idea behind this test setup is to create a TXT DNS record which will return one of possible three results depending on the Client DNS resolver and EDNS0-Client-Subnet provided location:

- US-West-2 for clients or resolvers located closest to the AWS region US-West-2 (Oregon) based on IP Geolocation data.

- US-East-2 for clients or resolvers located closest to the AWS region US-East-2 (Ohio) based on IP Geolocation data.

- Unknown for clients or resolvers where IP Geolocation data only indicates them to be somewhere in the US and therefore places them into Kansas.

In the test setup here the “Unknown” location for IP Geolocation data (yellow dot in Figure 2) is within the area that would be steered towards the US-East coast origin. Therefore even clients located in Portland, OR might get directed to the Ohio origin if their resolver’s or EDNS0-provided client subnet cannot be correctly located. Breaking these clients out separately in the test setup will allow us to visualize this issue later.

RIPE Atlas setup

Next we create a RIPE Atlas customized measurement that will leverage up to 500 randomly selected probes within the US against the DNS hostname that was setup for geographic routing with Route 53 above. We expect each probe to report back a result of either “US-West-2”, “US-East-2”, or “Unknown”.

Similar the same set of up to 500 US-based RIPE Atlas probes will be used in a second customized DNS measurement. This measurement will resolve the above introduced TXT-based record for thr special hostname of TXT o-o.myaddr.l.google.com. With this RIPE Atlas measurement we can find out for each probe whether EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) is supported and what the provided subnet is.

Also we can find out the IP address of the DNS Resolver for each probe as seen by the Authoritative Nameserver. This information is especially of interest for the case where the DNS Resolver does not support EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS).

Test Results

Overview

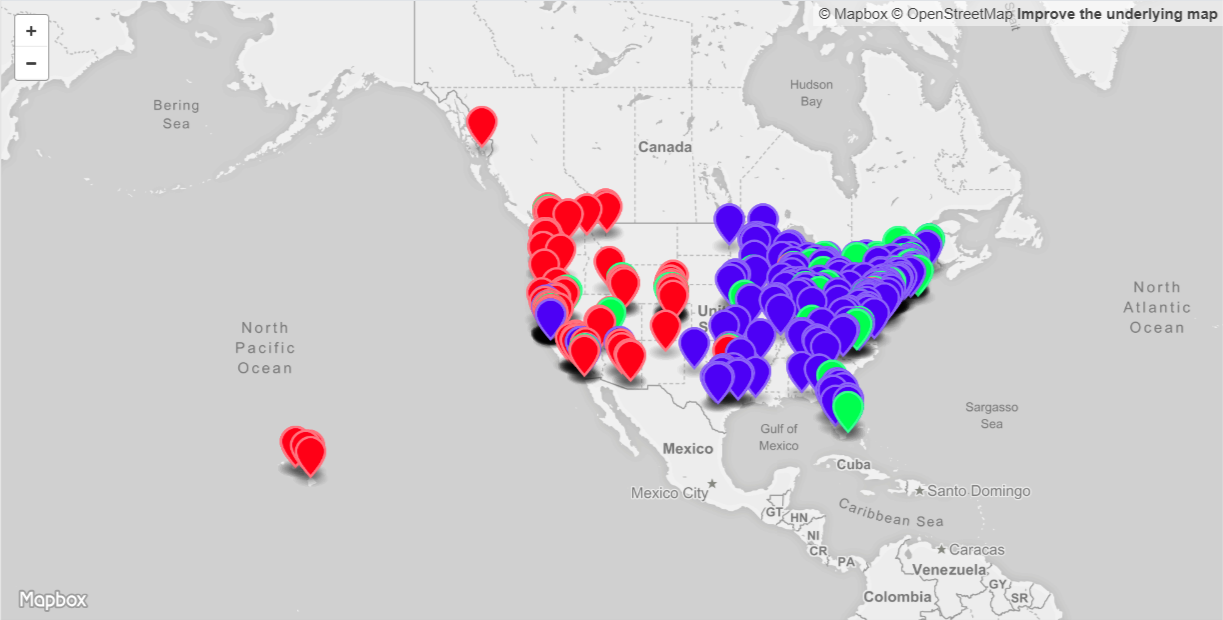

With some Python code the gathered results can easily be turned into a GeoJSON file (See Figure 3).

The location of each RIPE Atlas probe as reported by the probe’s host is leveraged in this visualization. The pin representing the location is colored in depending on the result for the Route 53 geographic routing test:

- Red pin: Represents a response by Route 53 of “US-West-2” and would therefore route traffic from this probe to the AWS US-West-2 (Oregon) region. In this setup this represents 29% of the probes.

- Blue pin: Represents a response by Route 53 of “US-East-2” and would therefore route traffic from this probe to the AWS US-East-2 (Ohio) region. Here this represents 59% of the probes.

- Green pin: Represents a response by Route 53 of “Unknown”. While traffic from this probe would also be routed to the AWS US-East-2 (Ohio) region, this is effectively due to Route 53 not being able to locate the probe beyond “somewhere in the US”. For this setup 12% of the probes could therefore not be located.

We can see that most of the US-East coast based probes would correctly route to the US-East coast origin (depicted in blue) and most of the US-West coast probes would also correctly route to the US-West coast origin (depicted in red). But we do see a few blue pins on the US-West coast, meaning that the corresponding probe would be routed to the US-East coast instead of the closer US-West coast. Similarly we also see a few red pins on the US-East coast. This clearly shows some non-optimal routing behavior. Later on we will look in more detail into the reasons for this behavior.

Probe Details

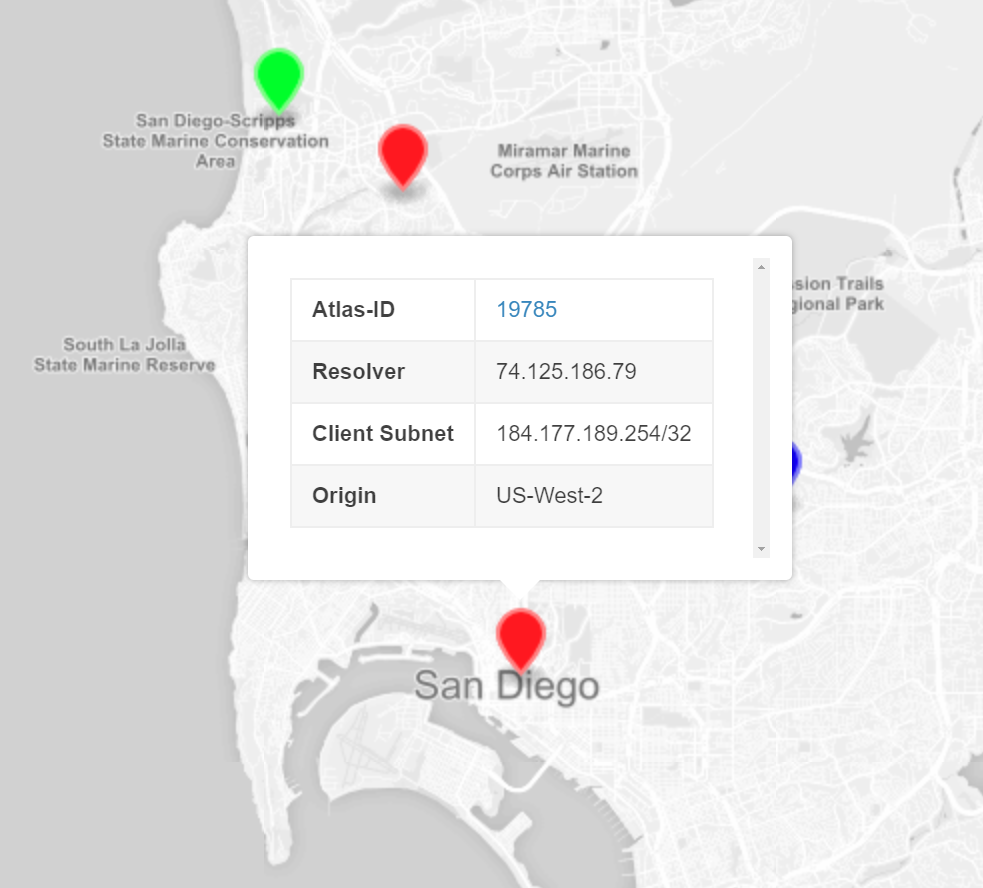

The way that I’ve setup the GeoJSON is to also display relevant information for each of the RIPE Atlas Probes (Figure 4).

After clicking on one of the pins you’re able to see:

- Atlas-ID: The RIPE Atlas ID of the probe linked to RIPE ATLAS API’s “Probe Detail” view.

- Resolver: IPv4 or IPv6 address of the DNS Resolver for the probe as seen by an Authoritative Nameserver.

- Client Subnet: EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) provided client subnet if supported by the probe’s resolver.

- Origin: Result of the DNS lookup against the Amazon Route 53 test entry. This will either be “US-West-2”, “US-East-2”, or “Unknown” and corresponds to the color of the pin.

Explore the GeoJSON

You can explore this GeoJSON yourself below, as it is published as a Gist to Github.

Give it a try and see what you’ll discover!

The good, bad and ugly

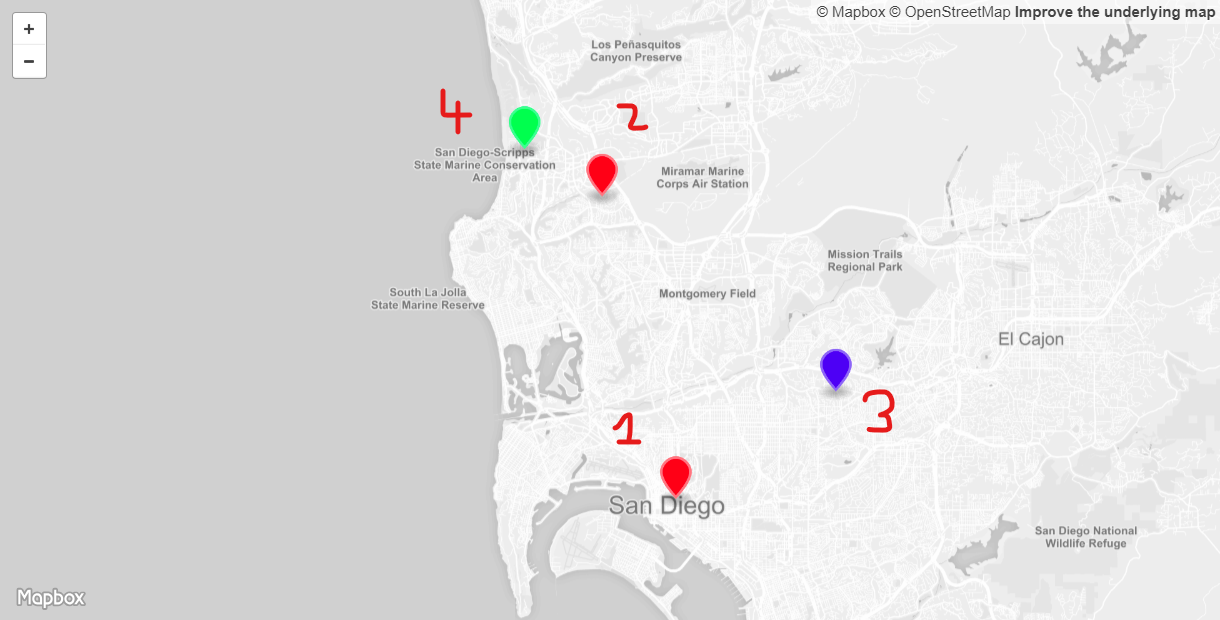

Let’s drill down on four RIPE Atlas probes to explore how geographic routing works and what the limitations are (See Figure 5).

These probes are all located in the San Diego, CA area and should therefore be routed to the US-West-2 location, represented by a red pin on the map. This location and the resulting probes were selected as they represent typical cases observed with geographic routing.

We will be using Maxmind’s GeoIP2 City Database Demo to lookup GeoIP data associated with the IPv4 and IPv6 addresses that are discovered for these probes as part of this test.

-

Location 1: This probe is correctly routed to the US-West-2 origin. The DNS Resolver IPv4 address for this probe is located in The Dalles, Oregon and also resides on Google’s Autonomous System Number (ASN). It therefore appears to be one of Google’s Public DNS Resolver nodes. Further we can see that for this RIPE Atlas probe the client subnet is provided. Using Maxmind the corresponding IPv4 address can be mapped to the location Coronado, California and the ISP to Cox. This location is therefore an excellent example for how the EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) improves the end-user experience, while using a DNS resolver that is physically located far away from the actual customer location.

-

Location 2: This probe is also correctly routed to the US-West-2 origin. Based on Maxmind data the DNS Resolver IPv4 address is located in Palo Alto, California and with the ISP WoodyNet. In this case the DNS Resolver does not support EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) and therefore Amazon Route 53 is forced to make a routing decision solely based on the DNS Resolver location information. Despite the geographic distance of a few hundred miles between client and DNS resolver, the DNS geographic routing is nevertheless correct here.

-

Location 3: This probe is incorrectly routed to the US-East-2 origin and therefore provides the end-user a reduced experience. The DNS Resolver’s IPv4 address is located in Saint Paul, Minnesota belonging to the ASN for Bethel University. The question why this probe would use a DNS Resolver from this organization and in this location is probably answered by looking at the RIPE Atlas probe’s name of Bethel Seminary. This name correlation lets us assume that there is a relation between the two. As with location 2, this DNS Resolver also does not support EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS). But in contrary to location 2, here the geographic distance between client and DNS Resolver is a few thousand miles. In this case Amazon Route 53 is also forced to make a routing decision solely based on the DNS Resolver location in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Therefore this probe is routed across the country to the Ohio origin instead of the more efficient Oregon origin. With DNS geographic routing based CDNs - like AWS CloudFront - the end-user experience is even more degradeded. Instead of leveraging a CDN Edge location in Los Angeles - less than 150 miles away - a CDN Edge location in Minneapolis, MN - more than 1,500 miles away - is being used. This added distance will lead to higher latency and lower throughput.

-

Location 4: This last location - at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) - cannot be identified by AWS Route 53 and is therefore routed incorrectly to the US-East-2 (Ohio) location instead of the closer US-West-2 (Oregon) location. Looking at the GeoIP information for the DNS Resolver’s IPv6 address we can see that Maxmind is indeed not able to locate this IP address beyond being somewhere in the US. Furthermore we can see that this DNS Resolver also does not support EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS). Looking at the RIPE Atlas probe’s actual IPv6 address, Maxmind is not able to locate this either. Therefore EDNS0-Client-Subnet (ECS) would not have provided any benefits here. Only the probe’s IPv4 address can be located correctly by Maxmind to be in San Diego, CA.This probe is an excellent example for Route 53 placing US-based clients or DNS Resolvers at the above mentioned Cheney reservoir location. And due to Cheney reservoir falling within the area that is closer to the US-East-2 (Ohio) origin, traffic is routed there.

Summary

This article provided a closer look at how DNS geographic routing - such as provided by AWS Route 53, but also leveraged by numerous CDNs - works. Using AWS Route 53 and RIPE Atlas we were able to visualize the real life results of a geographic routing DNS setup and dive deeper into some of the wanted and unwanted effects. A question that will need to remain to be explored in an upcoming post, is how these results compare to an Anycast based routing approach for the same set of Origins, leveraging e.g. the AWS Global Accelerator.