Limitations of Anycast for distributed content delivery

Notice: This article is more than 5 years old. It might be outdated.

In the previous article on Limitations of DNS-based geographic routing we have explored how DNS-based geographic routing works and especially what limitations you have to consider and accept, while using such a solution. In this article we will have a look at using Anycast instead. We will use the same set of origin locations within AWS and RIPE Atlas test probes as with the above referenced DNS-based geographic routing setup, to discover limitations of Anycast.

Anycast

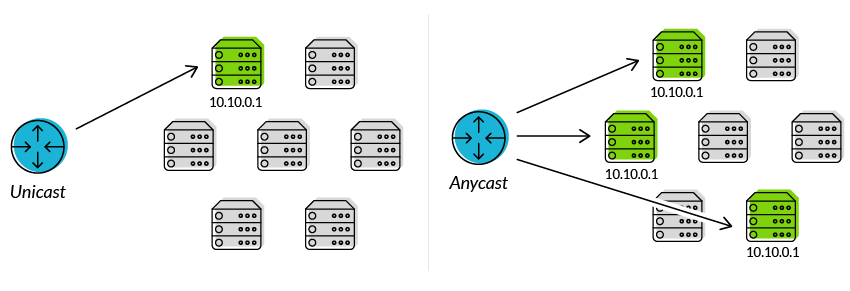

The network and routing methodology of Anycast provides multiple routing to multiple endpoints for a single destination. Routers will select the desired path on the basis of number of hops, distance, lowest cost, latency measurements or based on the least congested route. This is in contrary to the typical Unicast network and routing methodology, where each destination address uniquely identifies a single receiver endpoint (See Figure 1).

Anycast networks are widely used for content delivery network (CDN) products to bring their content closer to the end user, but also large public DNS resolvers make use of this concept. In the case of e.g. the Google Public DNS offering, the well-known IPv4 address of 8.8.8.8 is provided via Anycast from hundreds of Google locations, thus providing low latency DNS lookups from around the world.

AWS Global Accelerator

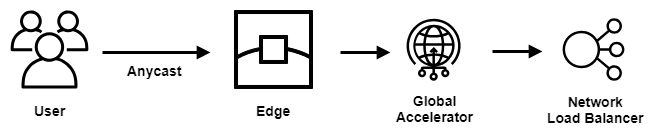

AWS Global Accelerator is a networking service offering from Amazon Web Services that aims at improving the availability and performance of the applications that you offer to your global users. It does so by using Anycast with a set of static IPv4 addresses that act as a fixed entry point into the AWS global network (See Figure 2).

When you set up AWS Global Accelerator, you associate anycasted static IP addresses to regional endpoints - such as Elastic IPv4 addresses, Network Load Balancers, and Application Load Balancers - in one or more AWS Regions. The static anycasted IPv4 addresses accept incoming traffic onto the AWS global network from the edge location that is closest to your users. From there, traffic for your application is routed to the desired AWS endpoint based on several factors, including the user’s location, the health of the endpoint, and the endpoint weights that you configure.

Note: As of today AWS Global Accelerator has very limited IPv6 support.

RIPE Atlas

In this post we will use RIPE Atlas to check the performance of a geographic routing enabled DNS entry.

RIPE Atlas is a global network of hardware devices, called probes and anchors, that actively measure Internet connectivity. Anyone can access this data via Internet traffic maps, streaming data visualisations, and an API. RIPE Atlas users can also perform customised measurements to gain valuable data about their own networks.

I highly recommend you to consider hosting a RIPE Atlas probe yourself. Not only will you benefit from the data that it collects on your Internet connection, but it will also allow you to run customized measurements against various Internet targets. And in the end every additional RIPE Atlas probe will benefit the overall Internet community.

Here we will be using RIPE Atlas customized measurements to investigate the performance of DNS-based geographic routing.

Test Setup

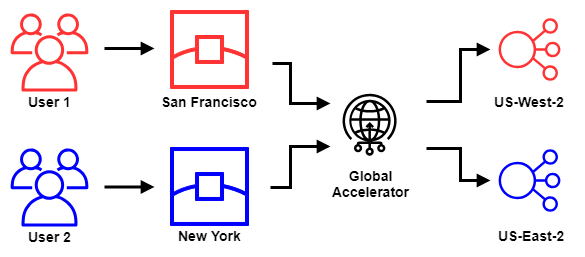

For this article the test setup will consist of fictional origins where we want to steer traffic to via geographic routing. The test will focus on the US with one origin in the US East coast and one origin in the US West coast.

While investigating DNS-based geographic routing, we were able to leverage the RIPE Atlas DNS test. Unfortunately here this test won’t provide us the information that we are looking for as Anycast doesn’t depend on DNS. Instead we have to leverage one of the other RIPE Atlas test mechanism. The SSL test will provide us a mapping of RIPE Atlas probe location to origin endpoint if we assign a different TLS/SSL certificate to each of the two origin locations.

AWS Global Accelerator Setup

For this test we will create a single accelerator within AWS Global Accelerator along with a single Listener. This listener is configured on Port 443 for the protocol TCP, as we want to make use of HTTPS for this test run (See Figure 3).

Before we can add Endpoint Groups and Endpoints, we have to actually create these endpoints. And as mentioned before we want to create these endpoints with a separate TLS/SSL certificate, so that we can differentiate to which origin a given RIPE Atlas probe was steered towards.

The easiest approach is to create a Network Load Balancer (NLB) with TLS termination and a certificate issued by AWS Certificate Manager. Again, keep in mind that the NLB in US-East-2 and the NLB in US-West-2 need to be issued individual certificates for our test.

In real life you would issue either the same or different certificates to the origin endpoint, but leverage the same common name, based on the DNS hostname that you configured for your Anycast addresses. As this is not a production setup, but a test, the actual certificate common name doesn’t matter here.

RIPE Atlas setup

The RIPE Atlas test is configured as a SSL measurement against one of the anycasted IPv4 addresses of your AWS Global Accelerator setup. As each of the anycasted IPv4 addresses is announced via BGP from the same set of AWS Edge nodes, it is irrelevant which one you pick.

Test Results

Overview

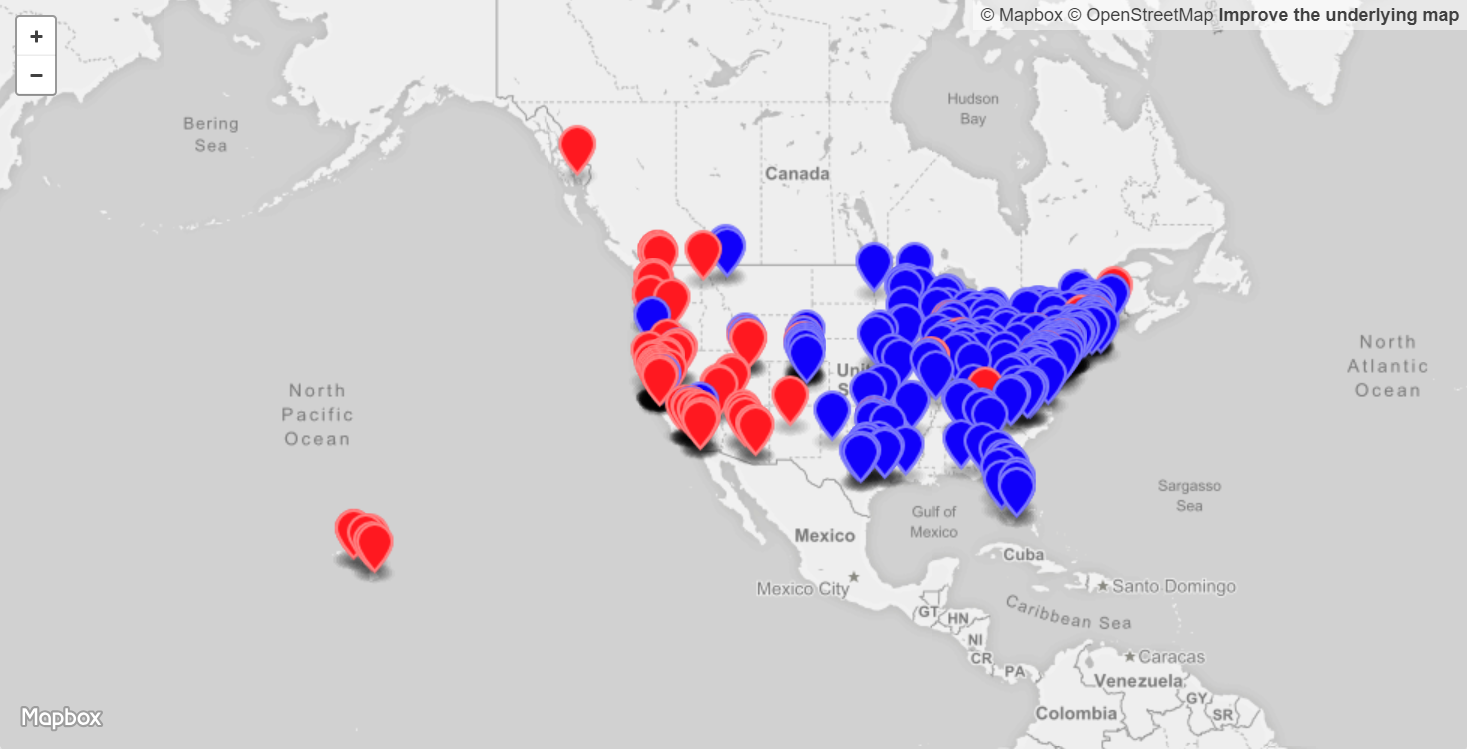

With some Python code the gathered results can easily be turned into a GeoJSON file (See Figure 4).

The location of each RIPE Atlas probe as reported by the probe’s host is leveraged in this visualization. The pin representing the location is colored in depending on the result for the Route 53 geographic routing test:

- Red pin: Represents a response with the SSL certificate that is assigned to the “US-West-2” origin. Traffic from this probe is therefore served by the AWS US-West-2 (Oregon) region. In this setup this represents 31% of the probes, which is 2 percentage points higher than with DNS-based geographic routing for the same set of probes.

- Blue pin: Represents a response with the SSL certificate that is assigned to the “US-East-2” origin. Traffic from this probe is therefore served by the AWS US-East-2 (Ohio) region. Here this represents 61% of the probes, which is 2 percentage points lower than with DNS-based geographic routing for the same set of probes.

We can see that most of the US-East coast based probes are correctly routed to the US-East coast origin (depicted in blue) and most of the US-West coast probes are also correctly routed to the US-West coast origin (depicted in red). But we do see a few blue pins on the US-West coast, meaning that the corresponding probe is routed to the US-East coast instead of the closer US-West coast. Similarly we also see a few red pins on the US-East coast. This clearly shows some non-optimal routing behavior. Later on we will look in more detail into the reasons for this behavior.

Probe Details

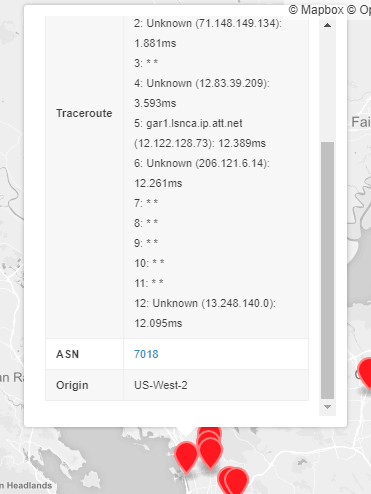

The way that I’ve setup the GeoJSON is to also display relevant information for each of the RIPE Atlas Probes (Figure 5).

After clicking on one of the pins you’re able to see:

- Atlas-ID: The RIPE Atlas ID of the probe linked to RIPE ATLAS API’s “Probe Detail” view.

- Traceroute: Traceroute results from the RIPE Atlas probe to the AWS Edge location serving the anycasted address.

- ASN: The Autonomous System Number (ASN), allowing you to identify the Internet Service Provider of the probes host.

- Origin: Result of the certificate lookup against the entry. This will either be “US-West-2” or “US-East-2” and corresponds to the color of the pin.

This setup will later help us drill down deeper into some of the RIPE Atlas locations that showed sub-optmal routing behavior.

Explore the GeoJSON

You can explore this GeoJSON yourself below, as it is published as a Gist to Github.

Give it a try and see what you’ll discover!

The good, bad and ugly

Let’s drill down on two RIPE Atlas probes to explore the limitations of Anycast routing.

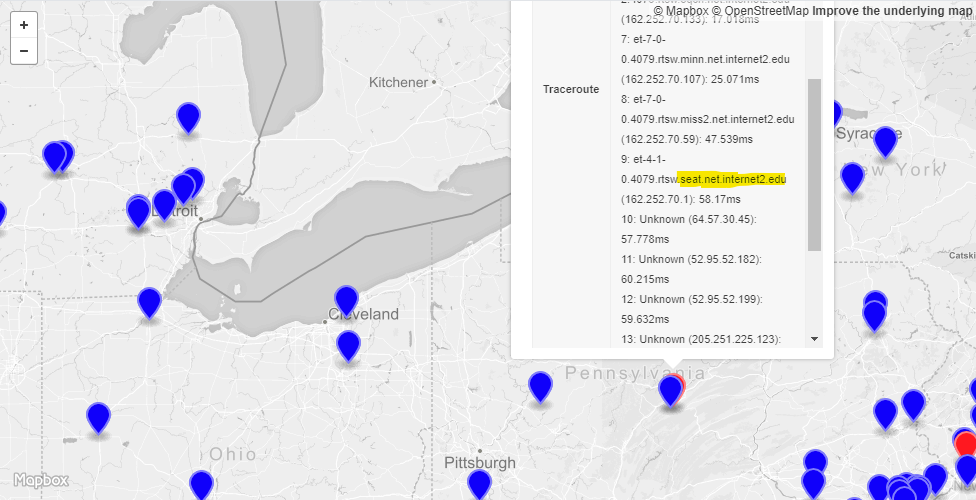

The first case is for a probe at the PennState university in University Park, PA. While this location is only around 500 km away from the AWS US-East-2 (Ohio) region and around 4,500 km from the AWS US-West-2 (Oregon) region, the probe is steered to the US-West-2 (Oregon) region by Anycast. Looking at the Traceroute results for this probe, we can see that it uses the Internet2 Network, an IP network that delivers network services for research and education. Further we can see that the Internet2 Network peers with AWS at Seattle Internet Exchange (SIX) in Seattle, WA (See Figure 6).

Looking at ASN 3999, the ASN for the Pennsylvania State University, we can see IPv4 peering with two different Internet2 ASNs. There is ASN 11537, which participates in a single public Internet Exchange. Also there is ASN 11164, which participates in 10 public Internet Exchanges.

It appears that the Pennsylvania State University - potentially due to financial reasons - made the decision to route all IPv4 traffic to AWS via ASN 11537 and therefore the Seattle Internet Exchange, leading to increased latency for accessing AWS’ US East coast regions as well as CDN PoPs.

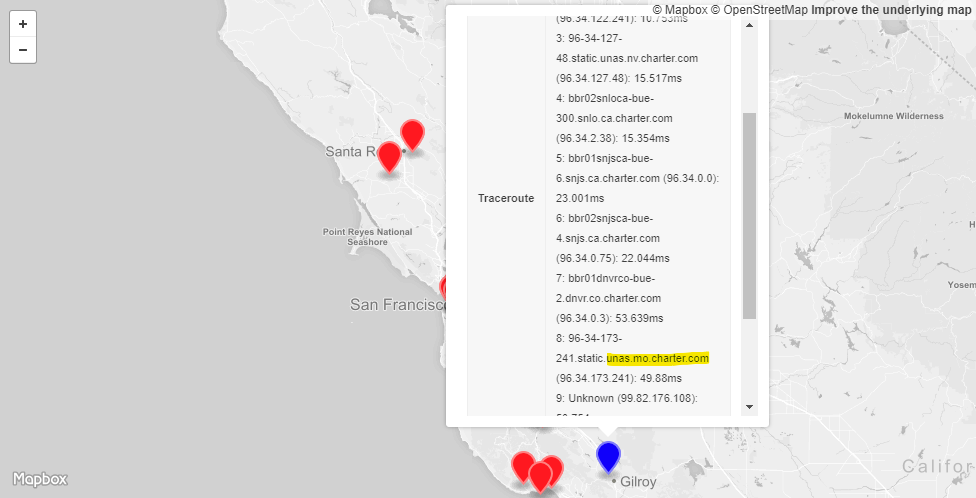

Next we have a RIPE Atlas probe whose host is a customer of Charter Communications. Here we can see that Charter routes the traffic from this Gillroy, CA based customer via Denver, CA and St. Louis, MO to the AWS Edge at an unknown location (See Figure 7).

Once again this routing decision could be based on financial reasons. Nevertheless Charter’s customer in this case will experience higher latency and therefore a reduced experience as a result of this decision.

Summary

This article provided a closer look at the limitations of Anycast routing. Using AWS Global Accelerator and RIPE Atlas we were able to visualize the real life results of Anycast-based routing and dive deeper into some of the unwanted effects. Also we were able to contrast these results with a similar DNS-based geographic routing setup. Similar to the test setup of DNS-based geographic routing, even with an Anycast base approach we see inefficient routings, where customers are directed to leverage an origin across the continental US even though another origin is closer by. But what performs better, DNS-based geographic routing or traffic steering via Anycast? Overall it appears that both perform in a similar way with each having some corner cases that provide a reduced end-user experience.